Five Conversations with Taxidermied Animals

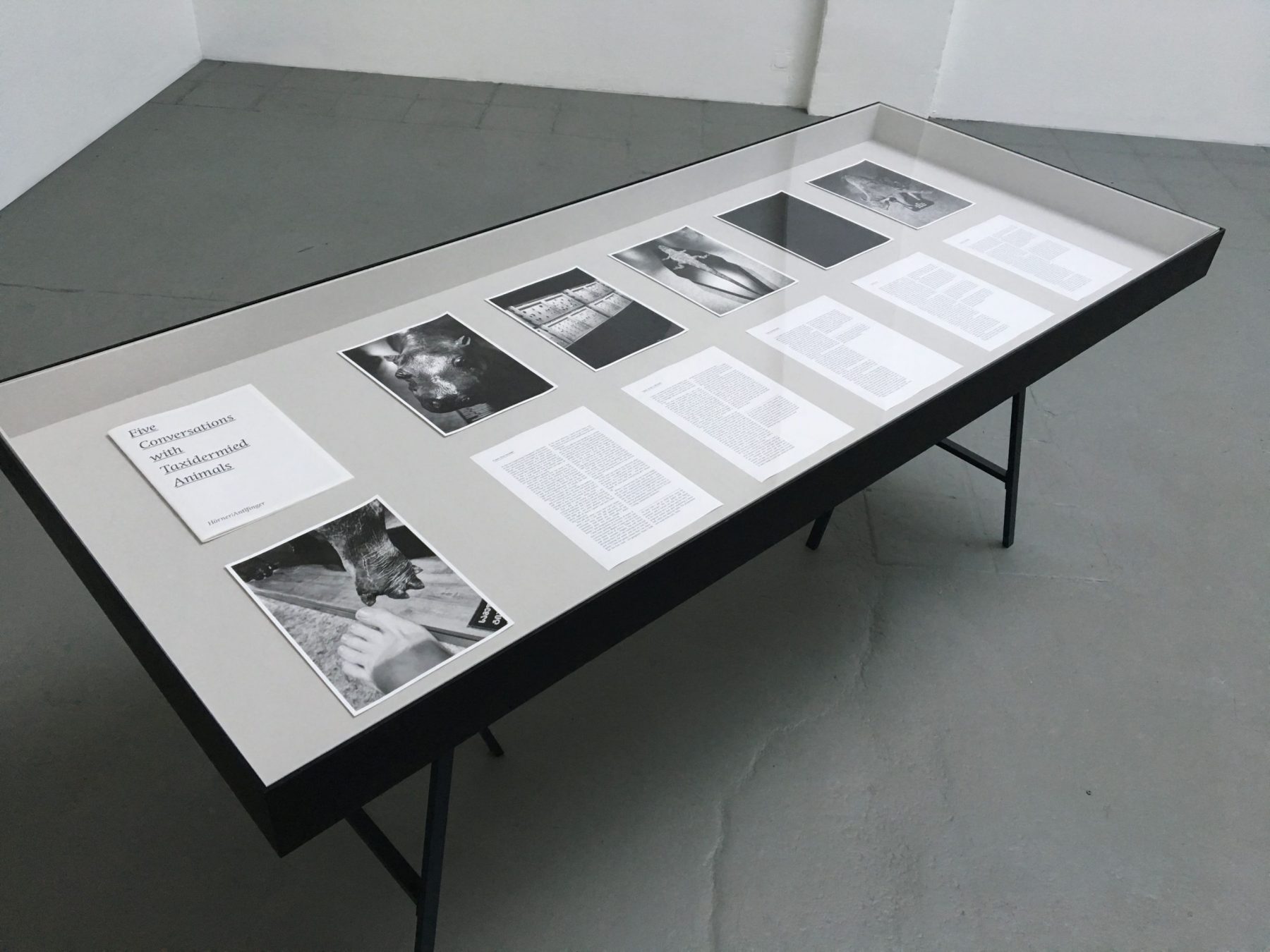

2017 Photos and transcripts in a glass case + Edition (108)

The blackbird sings its importance;

the babblers dance their shining prestige;

the storytellers crack the established disorder.

– Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble

All non-human animals in natural history collections have a story. Their stories are often closely linked to that of human animals (albeit involuntarily) – many of them are from zoos. The classical museum narrative, similar to that of zoos, creates distance to animals as historical subjects by presenting their bodies as specimens of a particular species. In Five Conversations with Taxidermied Animals we have attempted to focus on the animal individuals behind the specimens – on their agency. To this end, we experimented with methods of obtaining insight (Erkenntnismethoden) that create a connectedness. A connectedness that is urgently required in order to understand what we see.

How animal biographies can be narrated, is a question that concerns, in particular, historians and social theorists in the field of Human Animal Studies. Because animals generally cannot speak for themselves, creating empathy for the animal subjects – radically adopting their point of view – is an option. Similarly to human individuals (e.g. slaves or women), whose voices were ignored or suppressed by historians of their time. But what if non-human animals could speak to us after all?

Animal communicators like Anna Breytenbach and Penelope Smith use mental techniques such as telepathy to enter into dialogue with animals. They communicate with wild animals to warn them about fires, help with the sometimes difficult integration of rescued animals into already existing animal groups at rescue centres and they mediate between companion animals and their humans. In doing so, they also cross the boundaries between life and death, for example when establishing contact between humans and deceased companion animals.

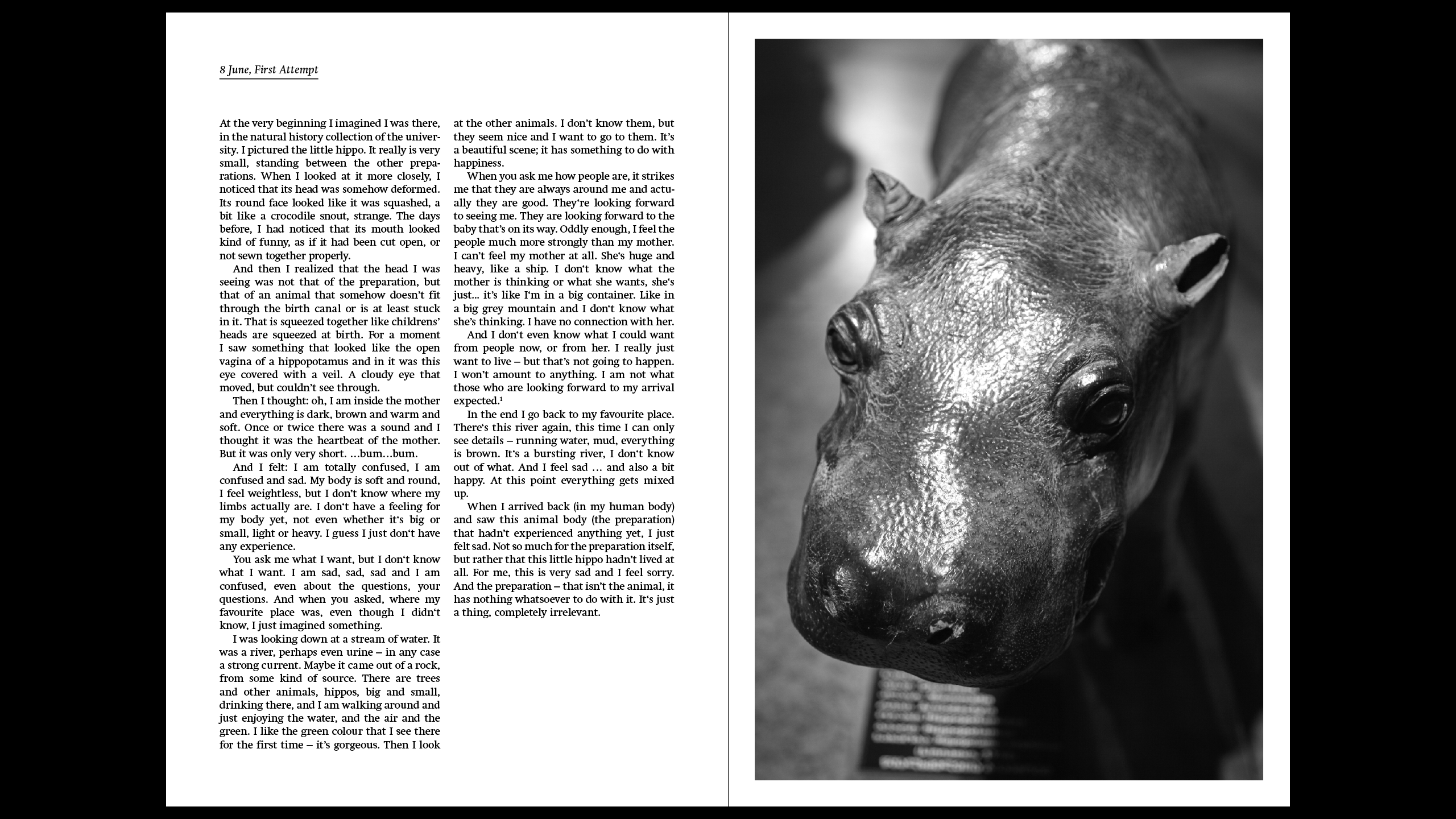

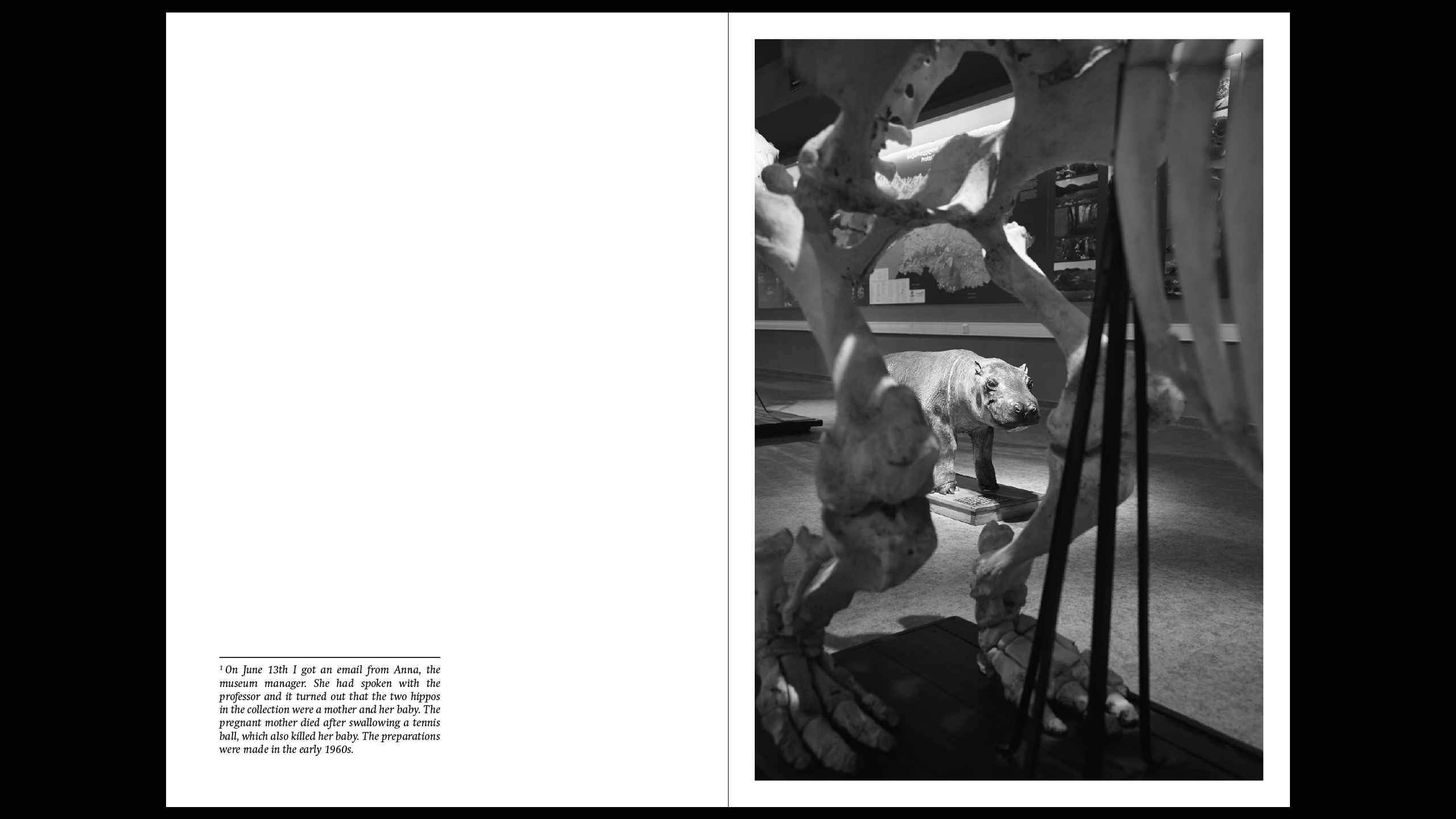

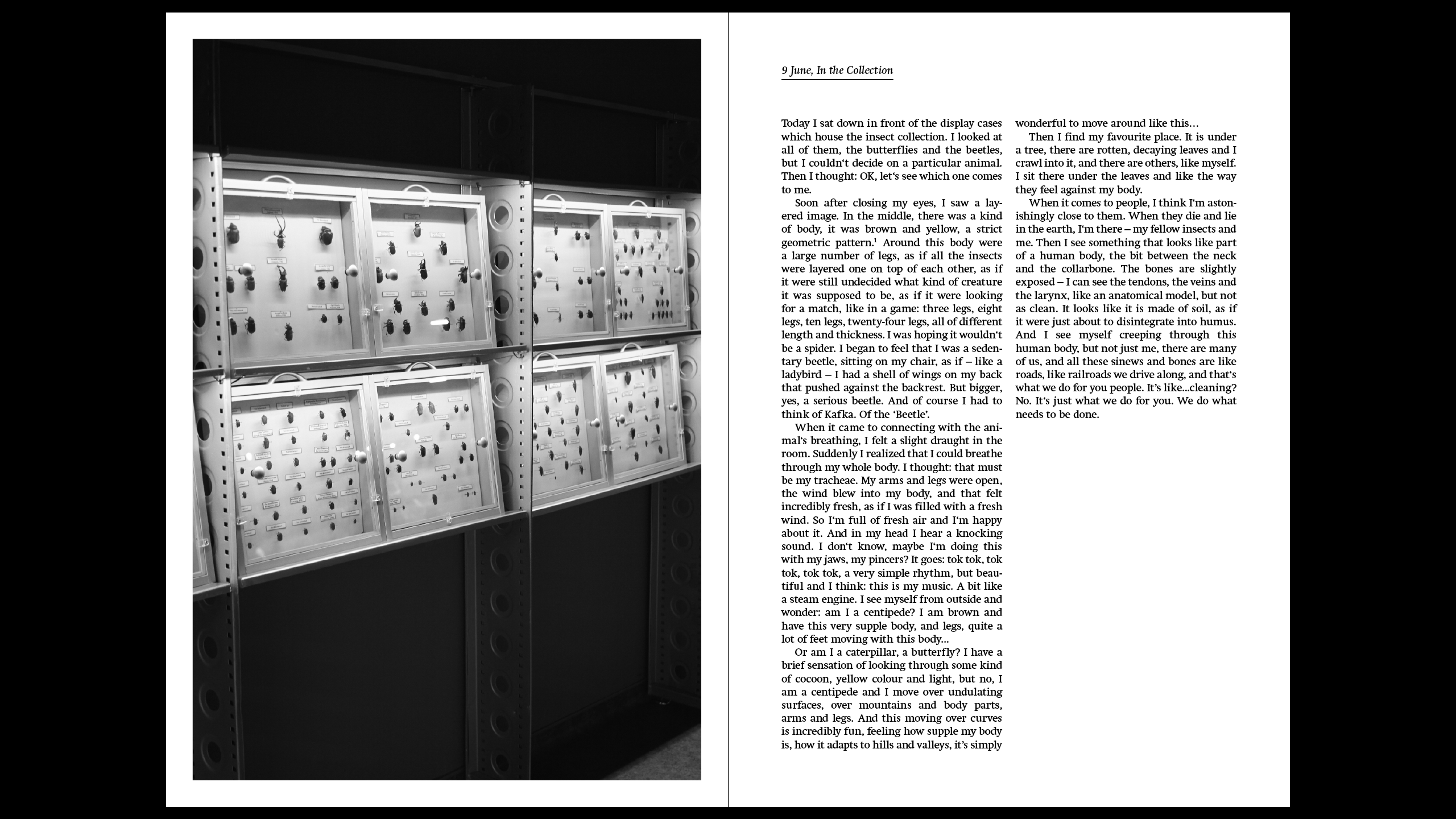

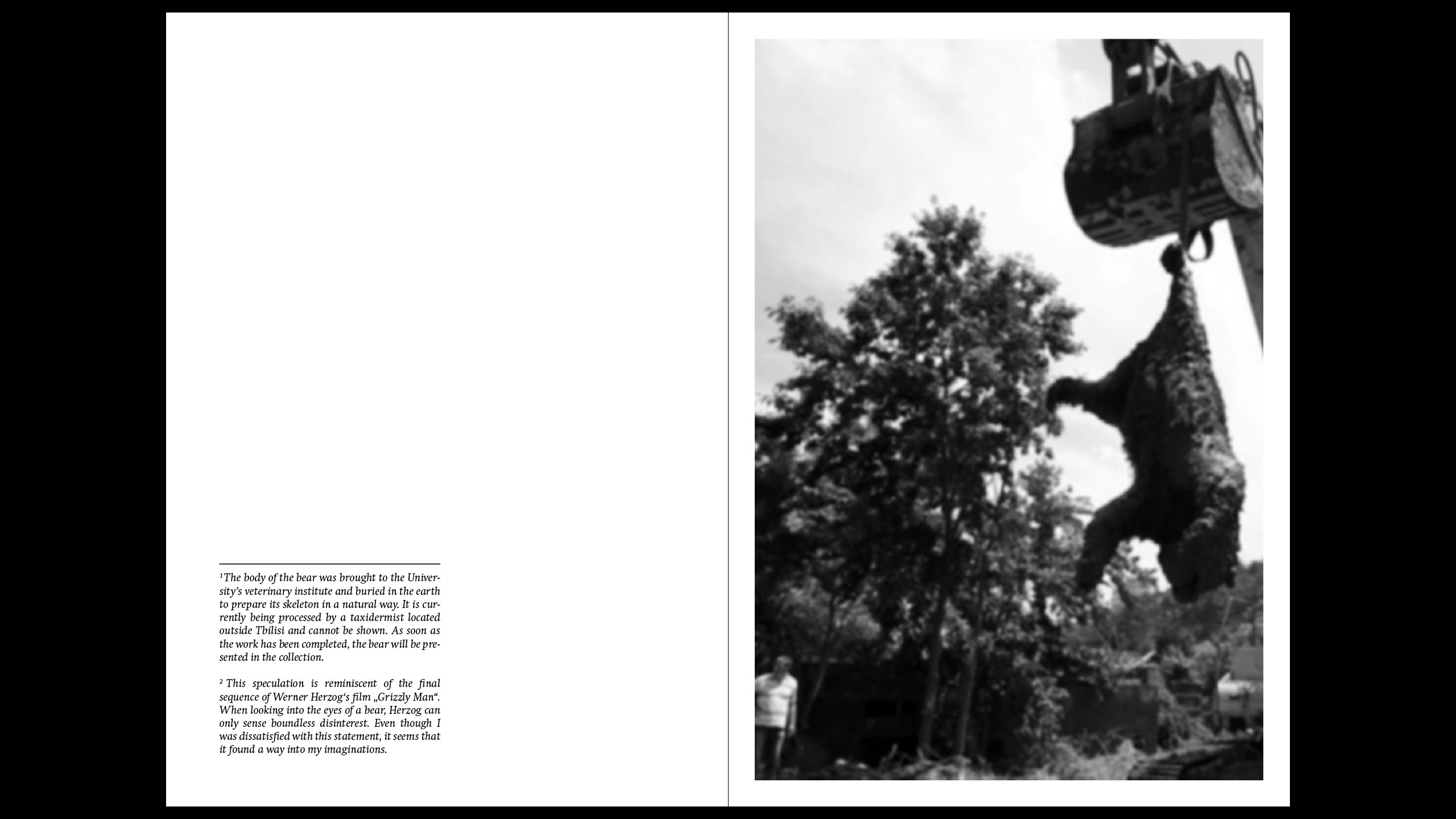

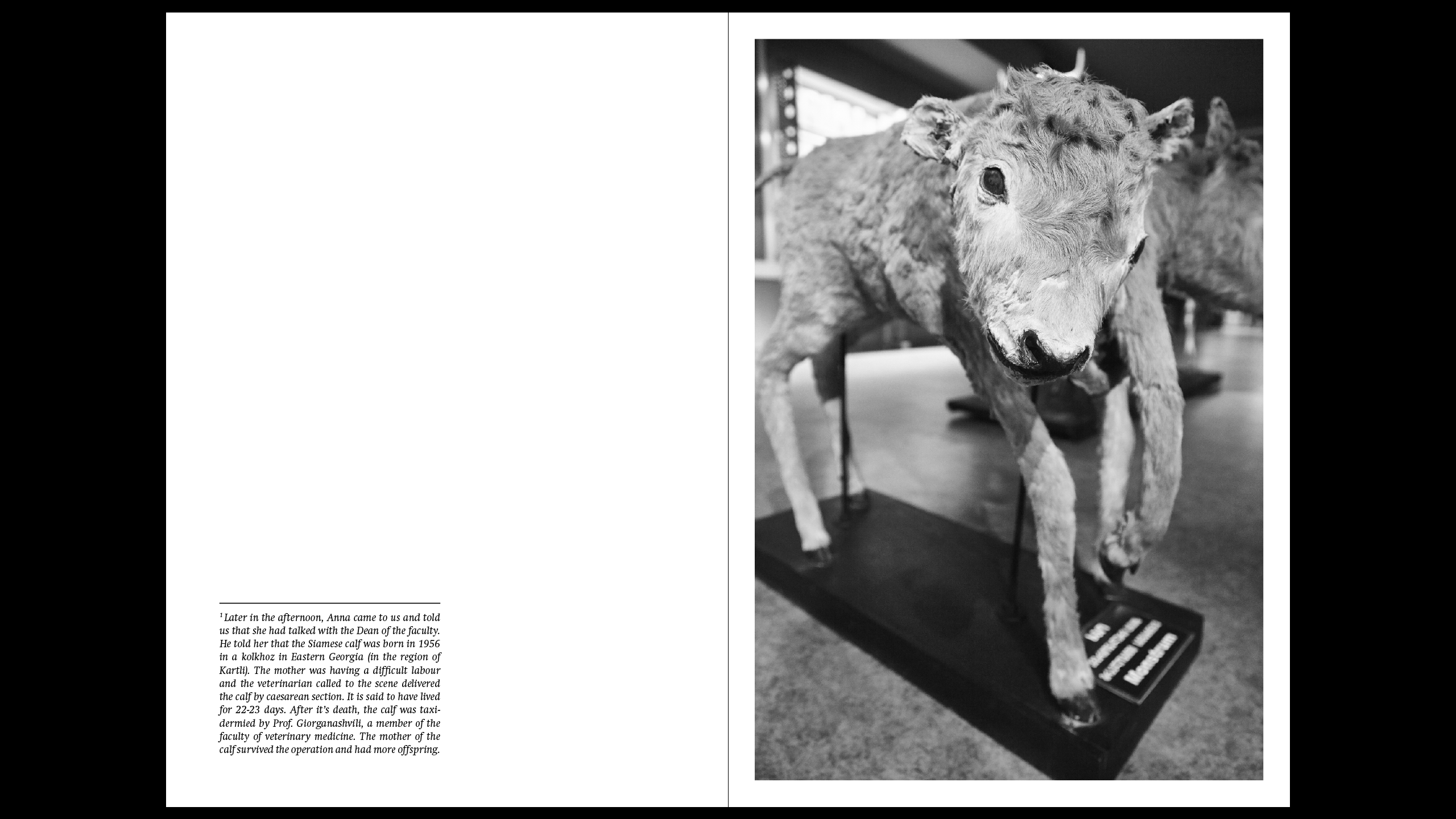

The Free University of Tbilisi boasts a small collection of both natural history and veterinary specimens and enabled us to undertake first experiments in this direction. Nana Ramishvili, director of the collection and her colleague Anna Veshaguridze were open to our ideas and actively supported our work. As a result of various faculties and collections being merged in the wake of Georgia’s declaration of independence and the dissolution of the GSSR (Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic), the majority of provenience records were lost. Although it was known that most of the animals originated from the zoo in Tbilisi, nothing was known about the circumstances of how they came to be part of the collection, e.g. what they died of, who dissected them etc.

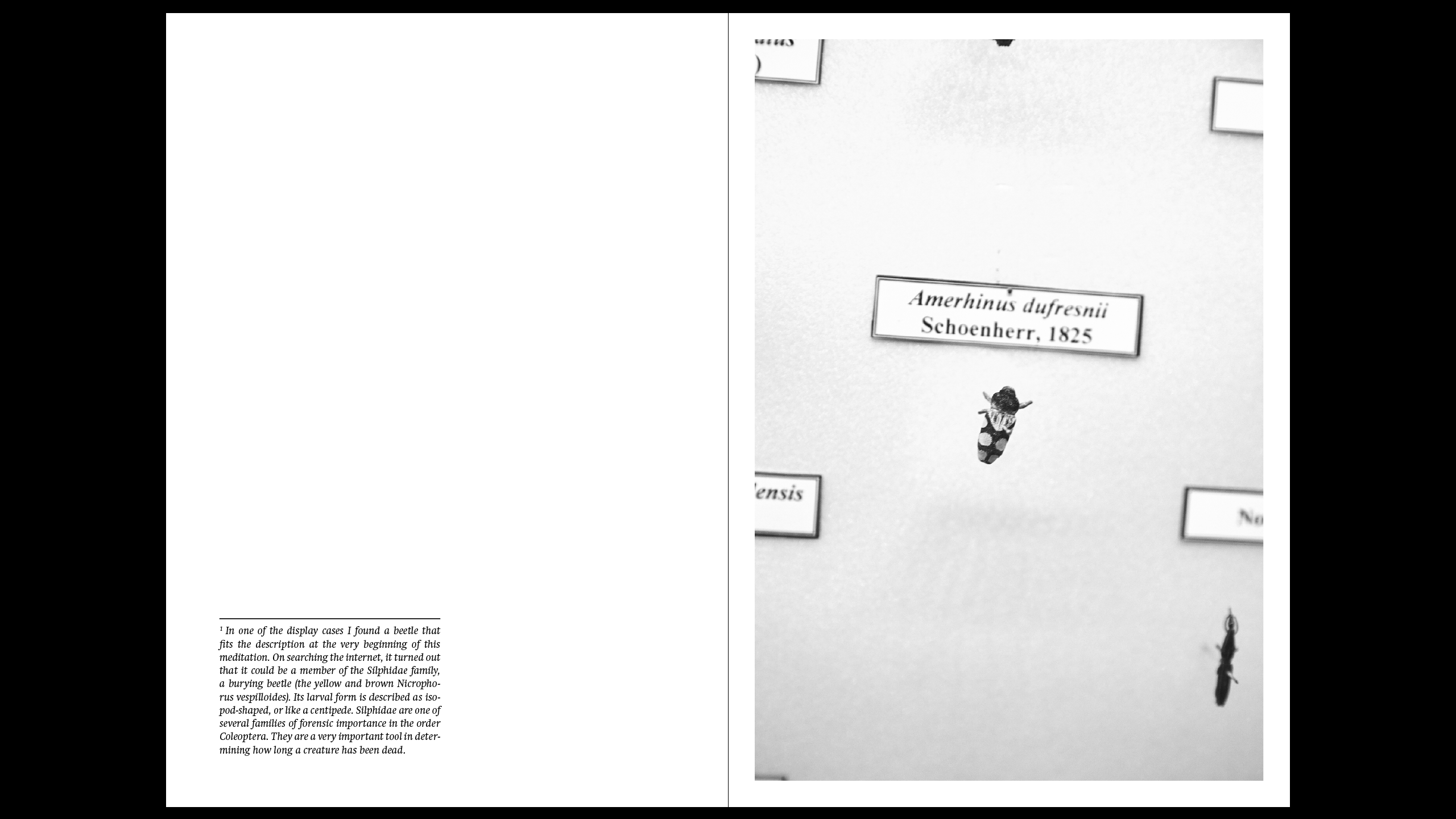

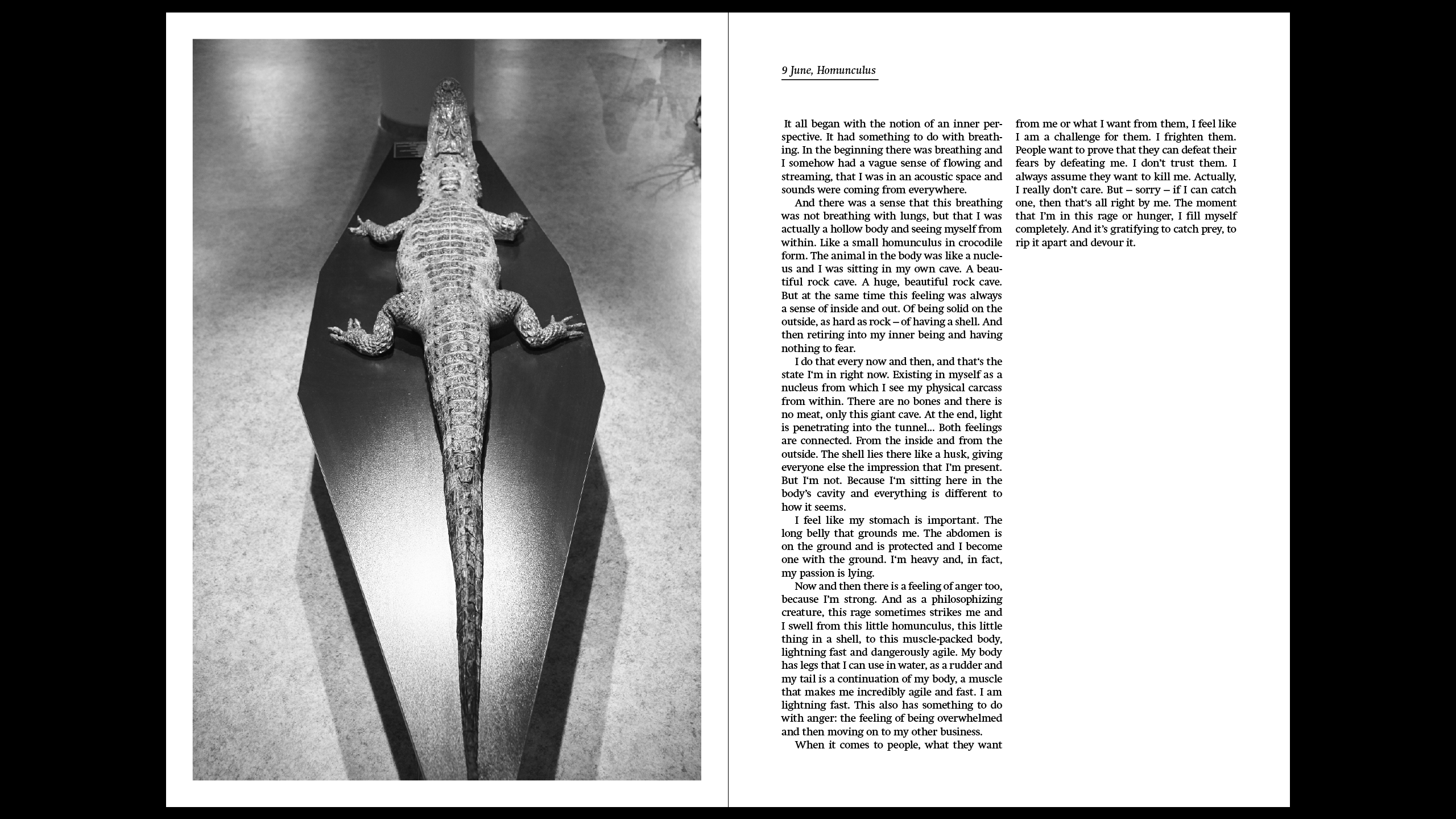

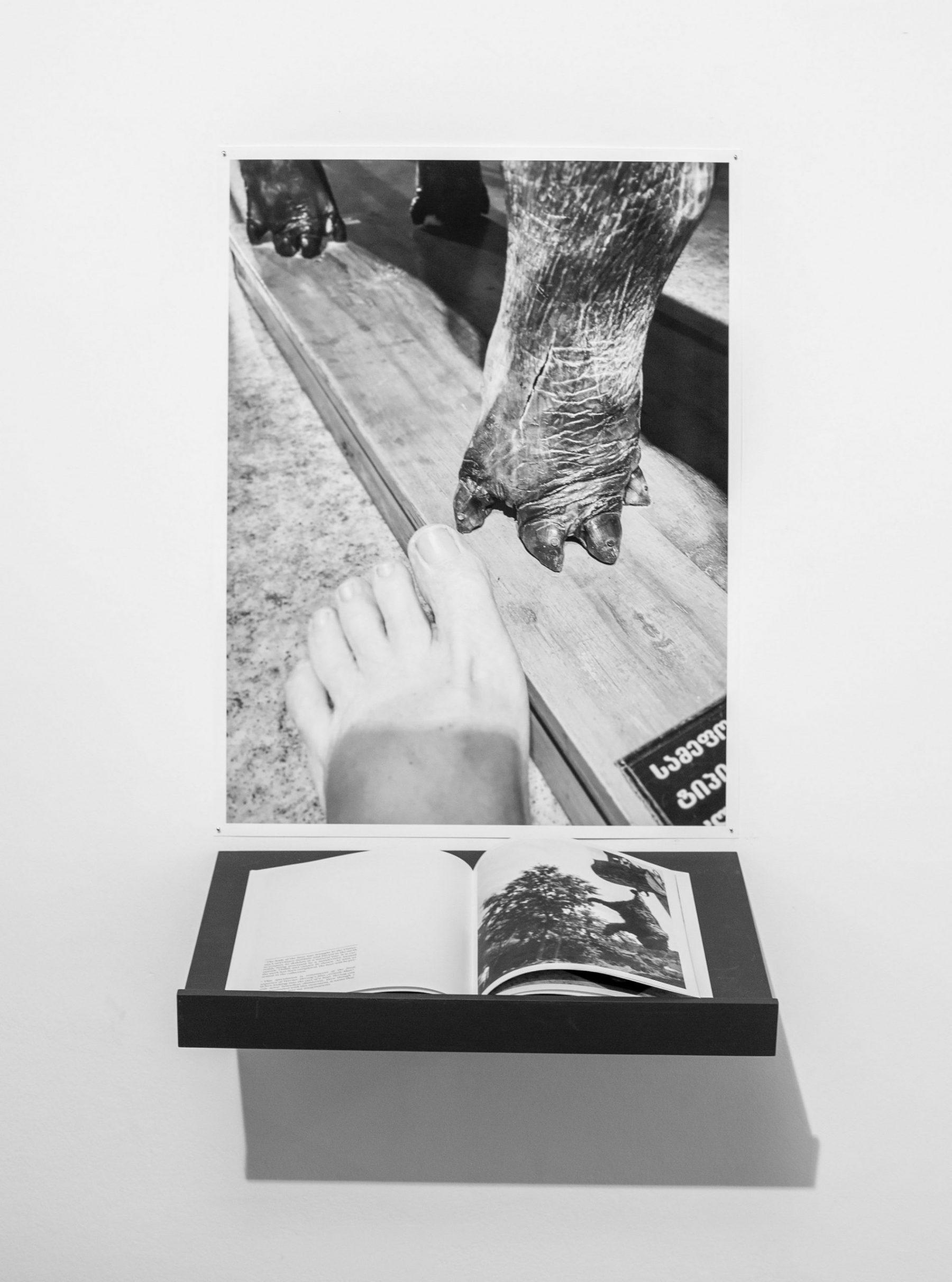

For our work we used a script provided by an animal communicator – a kind of guided meditation (also known as animal meditation) during which we politely approached those animals that had caught our attention while exploring the collection. To familiarise ourselves with the collection we began by photographing a large number of the specimens. Later we each chose one picture of an animal, with which we’d had contact, for the presentation. The texts are transcriptions of the perceptions, imaginations and knowledge we gained in the process of slipping into the body of the animal individuals. For a short time we were shape-shifters, we experienced the world from the point of view of these animals.

Parallel to our research the museum manager, Anna Veshaguridze, was able to unearth more information about the specimens. An elderly professor, whom nobody had previously questioned, was witness to the objects entering into the collection and was able to give information based on his memories. Thus, gradually a collective picture emerged. Whether or not our notes are constructed/fictitious or knowledge gained by telepathy, depends to a certain extent on what we believe is possible. Much of what we discovered during the meditations correlated with that which Anna found out parallel to our activities. But even if we are sceptical about poetic, telepathic and shamanistic practices as methods of obtaining insight, they can still enable us to see things that were previously hidden – and these are sometimes the most obvious.

We would like to thank both the Free University of Tbilisi, in particular Nana Ramishvili (Director of the Life Science Collection) and Anna Veshaguridze (museum manager), for the constructive collaboration based on mutual trust and the non-human animals that inspired this work, for sharing their images, ideas, feelings and thoughts.

Curator: Maria Wildeis

Funded by: Frauenkulturbüro NRW