Lacking Colour – “Animal Agency” and Discursive Emptiness in the Pictorial History of the Animal-Welfare Movement

Beginning, at the latest, with the “animal turn”2, the announcement of an “animal agency”, of a potency of the animal counterpart, has found its way into academic debates, and has directly influenced and changed those debates. In essence, it has questioned to what extent the omnipresence of the animal in everyday life influences human behaviour. In particular, its pictorial representation indicates the historical centrality of the “animal” in human thought and material creativity.3The animal-welfare movement of the 19th and 20th centuries also made use of the subject. How difficult it is to lend colour to the animal, in the proverbial sense, and how little the animal-welfare movement has succeeded in approaching the goal of assigning agency to animals in images and the use of those images, will be discussed in this essay. The artistic representation of the liberator topos, seen in the installations of Hörner/Antlfinger, addresses the question of how one can represent the “authentic experience”4 of being an animal that expresses itself in a process of “becoming animal”5, in which the boundaries between man and animal are constantly eroded until they become unrecognizable. Hörner/Antlfinger show that the image of the animal is always shaped after a human one. On the basis of selected pictorial representations from the animalwelfare movement, an historical summary of the use of illustrations and photographs in the service of the movement will be provided, as well as an analysis regarding the agency demonstrated by the protagonists in the images – both human and animal.

For the modern animal-welfare movement,6 the invention of photography constituted a revolution, making it possible to represent animals realistically. In particular, the anti-animal testing lobby of the late 19th century made use of large posters, on which animals also were pictured. The “also” must be highlighted here, since until then the human being was the central motif of the picture and thus largely determined its illustrative parameters. Yet despite the technical developments, graphic representations remained dominant; these were intended to help to illustrate the harmonious coexistence of man and animal and to affirm one’s own humanity. Humanity thus began with the demonstration of the power relationship between man and animal, in which the paternalistic treatment of the “other” was stressed.

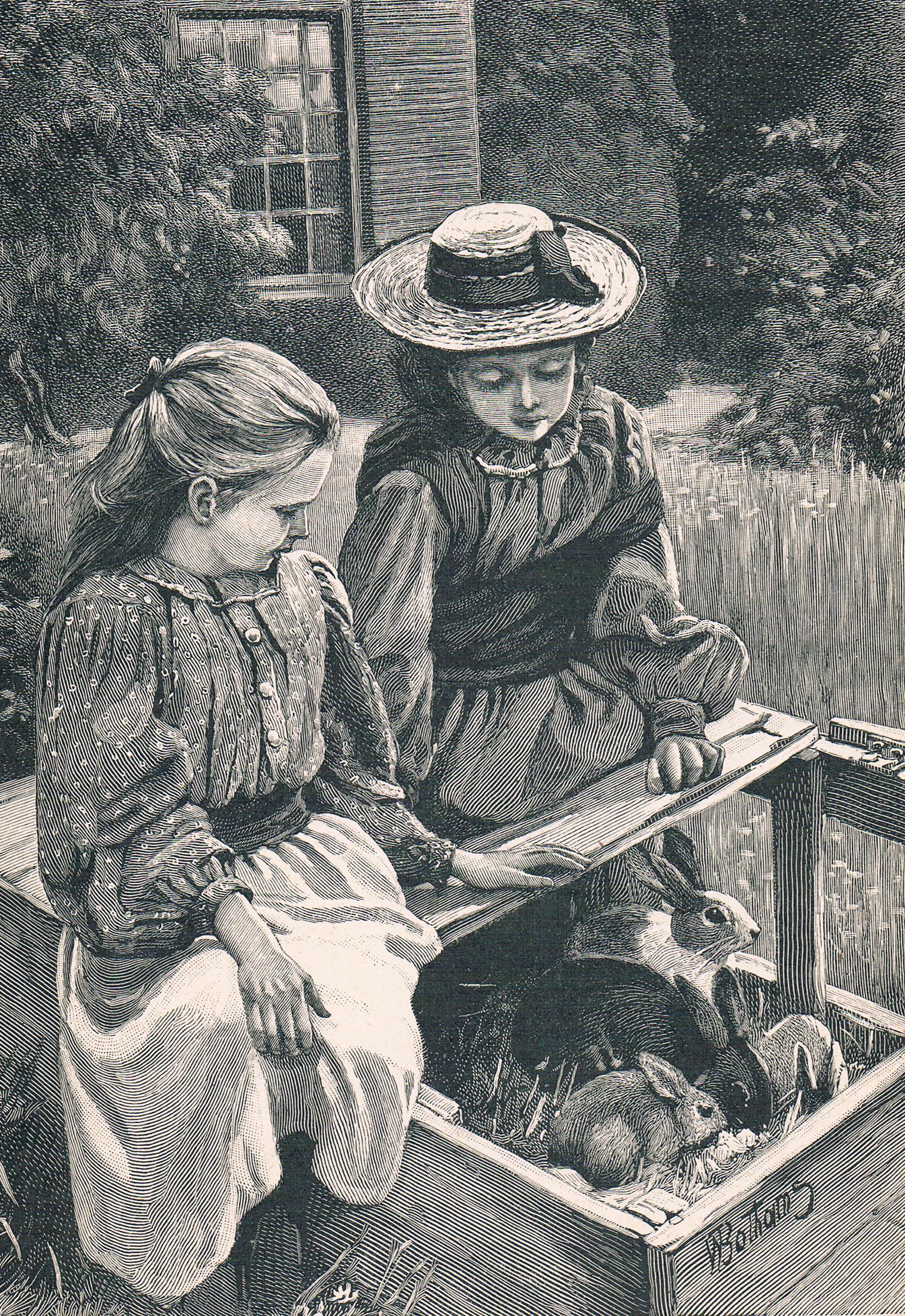

When animals were depicted as the central, meaningful motif in a picture, it was either as aesthetic objects, whose beauty was to be maintained by human beings; as exemplifications of romantic ideas about nature; or as subjects of fate, given over to the human hand either to caress or to injure – depending on the picture’s thematic charge – and in this way clearly subordinate to humans hierarchically (see Fig. 1).

The first category showed especially animals that were “improved” by breeding procedures or whose bodies were needed for hunting and killing and in this way took on a central meaning in the “becoming human” process.7 The illustrations of vulnerability and solicitude were mostly created by depicting animals and children together (Fig. 2).

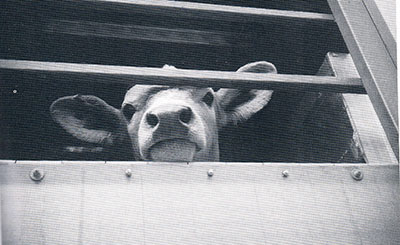

Progress in photography ran parallel to the development of automated procedures that brought extreme changes to the animal world and led to modern-day factory farming.8 At the same time, however, it gave the animals different minor roles. In their discursive impact, these differed only peripherally from those that previously were dominant in drawings or paintings. Just as before, animals adorned every image that made them into central figures of the civilising trope. It was not by chance that, especially during the Second World War, the animal-welfare organisations illustrated their materials with photographs of animals and members of the armed forces (Fig. 3). If the animal was already viewed as worthy of protection by soldiers, how then was the human population seen?

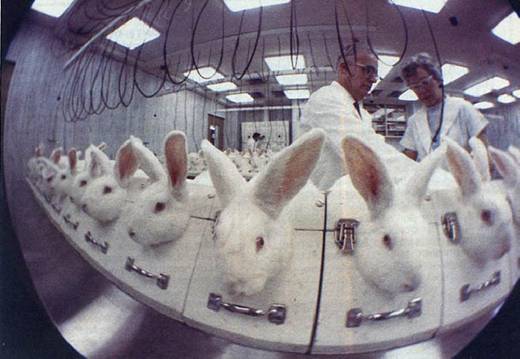

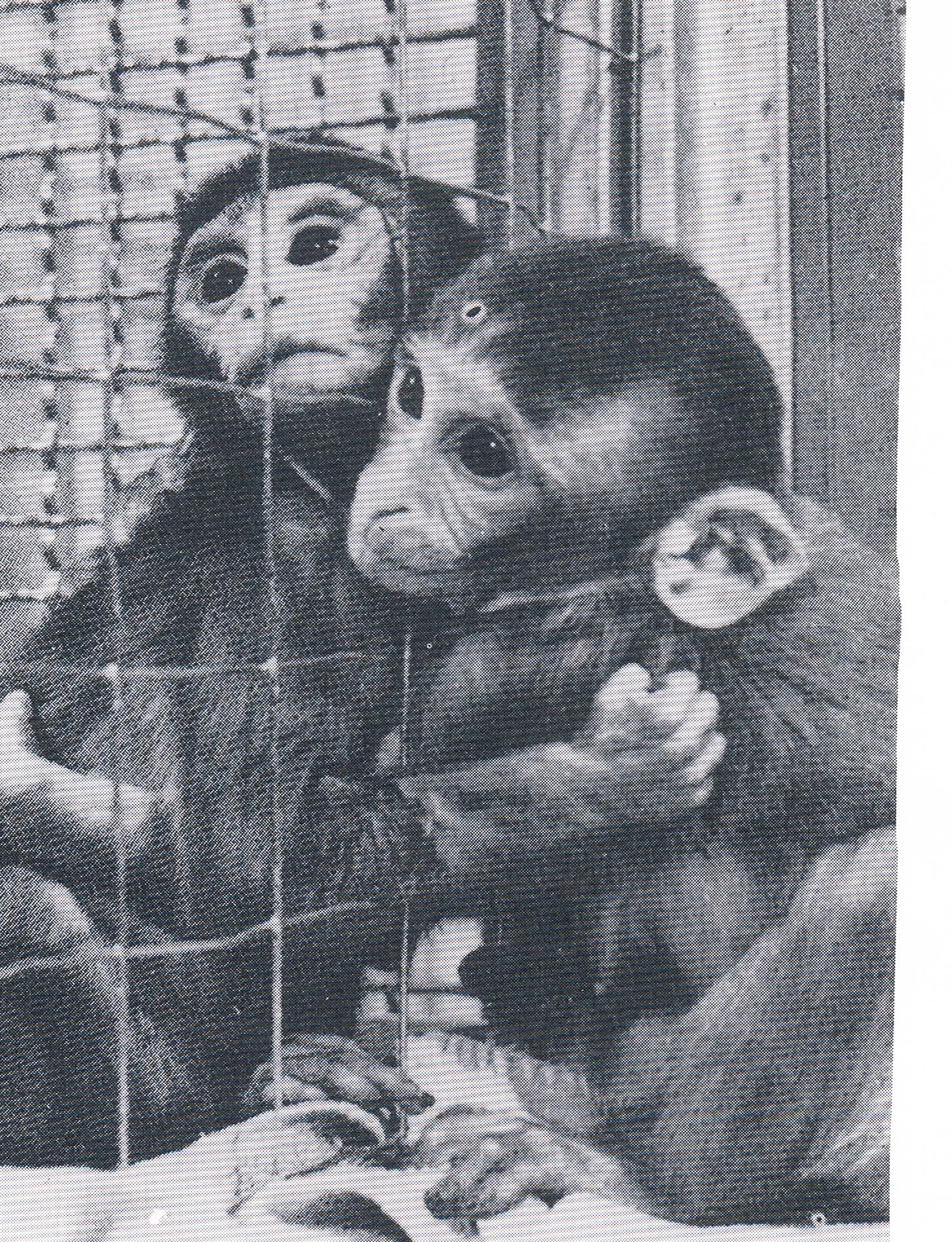

However, there were other popular images in which photographs were supposed to illustrate reality. Especially the photographs of animals in their “natural environment”, which were attempted by conservation-minded animal-welfare activists, naturalised the aesthetic preferences of human beings.9 In photography, as Ute Eskilden stresses, animals are lost not only because of the technical restrictions of the medium but because they are not allowed to be truly themselves. Instead, they are always representatives of a human “agency”.10 Hence, although we remember the images in which animal babies appear to plead with us with their eyes, there are no real animal actors behind these images but instead placeholders for culturally determined emotional fantasies. The baby-face scheme implies a “perfect analogue”, which silences the animal’s true self or acts as the “functional equivalent” of human projections.11 The animal “nomads” around as an object “according to the intention of the image creators”12 and, depending on the “historically specific perceptual horizon”,13 is read discursively in a different way: It is “encoded, decoded and newly encoded”.14 Especially the poor mistreated animal allows us to act out “thought and experience patterns of pity and rescue”.15 This eye-catching imagery is supported by a corresponding semantic ingredient. Yet someone always speaks for the animal; its interest is reproduced as one’s own (Fig. 4).

Especially in the photographs of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF), animals are promoted as a “quasi-natural embodiment of politically desired attitudes”.16 Here the focus is on the liberators and their mythical deeds. There is a clear visual shift towards the human person, which led to a fetishisation of the masked liberators within the animal-rights movement. The “animal” frame of reference is, so to speak, essential here, in order to prevent viewers from making analogies to terrorism (Figs. 5 and 6).17

Even though individual species and animals appear in these images, we always see only “collective images”18 of animals. Not only has their appellation been reduced to a generalised singular term (the animal), as Derrida complained,19 but the perception of them takes place almost without exception through exchangeable symbolic figures. Among these iconic figures, certain species are interchangeable. Whether a hamster, a rabbit or a cat is seated on the arm of the liberator is completely irrelevant to what the image is trying to convey; in the pictures of animals destined “for slaughter”, the principle of interchangeability is even essential, not only for the pictorial abstraction itself but also for its use.

The fact that animal-rights activists rarely make use of – undoubtedly available – material showing animals crammed into small cages, is connected on the one hand to the invisibility of this collective and on the other hand to the aggressive reluctance of the populace to allow such images to spoil their appetite for meat. What is lacking here is the right strategy to make this invisible collective visible. In the installation Factory≠Farm, this is illustrated in an especially impressive manner. Animals become dots on a digital map display, which seem to meander back and forth aimlessly.

In the sum of the whole, the absence of individual parts no longer stands out. Here the “superorganism” of a barn is not made up of individual animals but of material that has long since been generally regarded as dead meat. The swarm of the collective functions without the active participation of individualized actors; to the contrary, it actually requires their “de-subjectification”. Moreover, the purely artificial environment of modern factory farming arouses no memory of the animal images conveyed to us by the media since our early childhood: The marginalization of the animal succeeds because there is no recognisable counterpart that we can awaken from our memory.20 Also for this reason, the animal-welfare movement rarely makes use of such imagery. In addition, the collective mass is often interpreted culturally as a threat, and hence is not necessarily likely to appeal to people’s empathy.21

The difficulty the animal-welfare movement also has individualising animals in images and thus making them into actors shows how deeply engrained this collective is in our imaginations and how much, also here, the “anthropological machine”22 does not humanise the animal as a sum of the species. There are only a limited number of ways of interpreting such machine images, none of which attribute an actor status to the animal.

One of these interpretive patterns includes, in contemporary illustrations as well, the motifs of fatalism and suffering. The creature’s pleading look turns the human addressee into a powerful entity in the image-viewer constellation. The “iconography of the eye”23 focuses on the human observers, who are implicitly invited to become active. Even in an illustrative or discursive sense, the animal’s struggle for its own liberation, its emancipation from human beings, is not foreseen (Figs. 8 and 9).

Moreover, species that are easy to anthropomorphise are chosen, those with large eyes and recognisable facial structures. In this way, they remain a “disputed territory of the attribution of human hopes”24 and other human emotions. This humanlike glance prevents us from perceiving animals as animals.

One photographic genre that has caused a particular sensation during the last 20 years has managed without any animal at all. These poster series, which are used especially by the international animal-rights group PETA, show mostly beautiful, scantily clad specimens of the human species, who act as advertising vehicles. If an animal is included in one of these images, it serves only as decoration and as an indication that the image does not have a pornographic intent. The logical conclusion, as shown in Fig. 11, is that the included animal does not need to be a real one. The “naked ape” also manages to block out all animal-centred levels of meaning; the animal vanishes from the central experience of the picture.

As discussed above, in the propaganda of the animal-welfare movement, animal representations changed during the 19th and 20th centuries from projection surfaces of humanitarian self-expression to supposedly powerful actors. However, a closer look reveals that at the beginning of the new millennium, such representations are still linked to where they were at the start of the 19th century, with human beings as focal point and eye catcher. The subjectivity of the animal is not the main focus of its representation. Sometimes “agency” is even explicitly denied to the animal. On the one hand, animals are stylised as aesthetic objects, and on the other they act as placeholders of intra-human conflicts. This change does not proceed in linear fashion but is characterised by the respective positioning of the human in the “moving cosmos”. Animals are either made invisible, as evident in the animal industry’s practiced hiding of the suffering animal behind the advertising images of “happy cows and chickens”, or they are trapped in representations created by human beings.25

By verbalising or using dialogue to spotlight the connotations ascribed to the animal body, as Hörner/Antlfinger do in their three-part video „Rabbits—Getting an Idea of Something and Thinking Things Through to the End“, these animal pseudo-metaphors can become individuals, as part of the “becoming animal” approach. This type of artistic representation can succeed in making the animals appear both more colourful and more visible to the collective memory. For such an art might at least provide some impulses to people to show animals in a way that does not already determine their meaning.

Mieke Roscher

1. I thank Chris Wollard for the inspiration and for the title of this essay.

2. Harriet Ritvo, On the Animal Turn, in: Daedalus, Vol. 4, 2007, pp. 118–122, here p. 118.

3. Linda Kalof et al. (eds.), A Cultural History of Animals, Vols. 1–6, Oxford 2007.

4. Ute Eskilden, Kein Recht am Bild—Das fotografierte Tier, in: Ute Eskilden/Hans-Jürgen Lechtreck (eds.),

Nützlich, süß und museal. Das fotografierte Tier, Göttingen 2005, pp. 11–31, here p. 26.

5. See: Gilles Deleuze/Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis 1987, pp. 232 ff.

6. On the history of this movement, see: Mieke Roscher, Ein Königreich für Tiere.

Die Geschichte der britischen Tierrechtsbewegung, Marburg 2009.

7. Ron Broglio, Thinking with Surfaces. Animals and Contemporary Art, in: Aaron Gross/Anne Valley (eds.),

Animals and the Human Imagination. A Companion to Animal Studies, New York 2012, pp. 238–258, here p. 239.

8. Eskilden, 2005, p. 20.

9. Steve Baker, Picturing the Beast. Animals, Identity and Representation, Manchester 1993, p. 190.

10. Eskilden, 2005, p. 26.

11. Johannes Bilstein, Unsere Tiere, in: Johannes Bilstein/Mathias Winzen (eds.), Das Tier in mir.

Die animalischen Ebenbilder des Menschen, Köln 2002, pp. 13–43, here p. 19.

12. Eskilden, 2005, p. 30.

13. Thomas Macho, Der Aufstand der Haustiere, in: Regine Haslinger (Hg.), Herausforderung Tier. Von Beuys bis

Kabakov, München u.a. 2000, pp. 76–99, here p. 77.

14. Ibid., p. 94.

15. Bilstein, 2002, p. 18.

16. Rainer E. Wiedenmann, Spiegel und Fenster. Zur Semantik der Blicke in Tierfotografien, in: Eskilden/Lechtreck, 2005,

pp. 179–192, here p. 185.

17. Mieke Roscher, Gesichter der Befreiung – eine bildgeschichtliche Analyse der visuellen Repräsentation der Tierrechtsbewegung,

in: Chimaira – Arbeitskreis für Human-Animal Studies. Über die gesellschaftliche Natur von Mensch-Tier-

Verhältnissen, Bielefeld 2011, pp. 335–376.

18. Mathias Winzen, Das Tier als Bild, Vom Nutzen der Tiere für die Kunst, in: Johannes Bilstein/Mathias Winzen, 2002,

pp. 175–191, here p. 178.

19. See Jacques Derrida, The Animal That Therefore I Am, New York 2008, p. 23.

20. See, especially, John Berger, Why Look at Animals?, in: John Berger, About Looking, New York 1980.

21. Elias Canetti, Masse und Macht, Hildesheim 1992.

22. Giorgio Agamben, Das Offene, Der Mensch und das Tier, Frankfurt a. M. 2003, p. 46.

23. Wiedenmann, 2005, p. 187.

24. Amy Nelson, Die abwesende Freundin: Laikas kulturelles Nachleben, in: Jessica Ullrich et al.,

Ich, das Tier, Tiere als Persönlichkeiten in der Kulturgeschichte, Berlin 2008, pp. 215–214, here p. 217.

25. Kari Weil, Thinking Animals, Why Animal Studies Now? New York 2012, p.